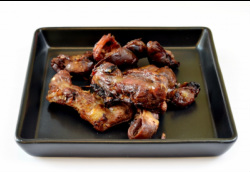

Roasted Liver. Photo credit: freedigitalphotos.net/Rakratchada Torsap

Roasted Liver. Photo credit: freedigitalphotos.net/Rakratchada Torsap

Odd parts

This column originally ran March 22, 2007, in The Woodstock Times, The Saugerties Times and The Kingston Times, etc.

If you’re a carnivore (if not you’d better turn the page quick), you have likely eaten offal, whether in juicy hot dogs or unctuous foie gras. Otherwise known as variety meats, specialty meats, organ meats, lips and a**holes, entrails, innards, the fifth quarter, quinto quarto in Italian, garbage, scraps, or fodder for Fido.

Although variety meats were popular in tougher times for their frugality, full flavors and pleasing textures, mostly we Americans are afraid of it, liking our meat in the form of nice tidy filets or boneless gristle-less squares that don’t look like they ever came from an animal. So offal has fallen out of favor lately, although it is enjoying a renaissance in cheffy circles. Anthony Bourdain’s Les Halles Cookbook (Bloomsbury, 2004) devotes a whole chapter to “Blood & Guts.” “Chefs get all misty eyed when they talk about it,” says Bourdain, unapologetically offering recipes for veal kidneys á là moutarde and pig heart á l’armagnac.

It’s had to find offal outside of restaurants, though. Although calves’ liver and sometimes tripe and oxtail are around, some things, like brains and lungs, are next to impossible to find. Variety meats are unpopular and don’t keep well, so much of it just goes to the dog food factory. People who live near Chinatowns are in luck, though, as the Chinese are great lovers of varied texture and flavor and specialty meats deliver. Some of them can be challenging to cook compared to steaks and chicken breasts, though, needing blanching (tripe), the briefest cooking (liver), or long slow simmering (oxtail), so some cooks are intimidated by them. “It takes love, and time, and respect for one’s ingredients to properly deal with a pig’s ear or a kidney,” said Anthony Bourdain in Fergus Henderson’s The Whole Beast: Nose to Tail Eating (HarperCollins, 2004). “And the rewards are enormous.”

Innards I have known

When I was a little girl we ate a lot more offal than our neighbors, maybe because of my southern-born parents. They would sometimes buy half a cow to freeze and so we often had beef tongue, which I loved for its mild flavor and fine texture. Later I came to adore dainty jarred pickled lamb tongues and the tongue sandwiches from Carnegie Deli in Manhattan, nearly as good as pastrami. I tried duck tongues at a Taiwanese restaurant in Queens but they were bony and tricky to eat.

Another frequent staple at my childhood table was lamb kidneys with green peppers, which I was never nuts for but would eat anyway. I never see them in stores; maybe people associate them with the urine they process, although supposedly a 12-hour soak in water followed by a 12-24 hour soak in milk solves that problem. Bruce Cost in his Asian Ingredients (Quill, 2000) calls pork kidneys “the world’s most wonderful entrail.”

Whenever my father made fried chicken there would be chewy gristly gizzards to nibble before the big pieces were done, and I loved those. Every Thanksgiving gravy had tiny dices of turkey gizzard and liver and although I detested liver I loved it anyway. I still do my gravy this way. And duck gizzards en confit (cooked in duck fat) are a divine way to top a salad in France.

Sometimes in a bag of gibbies you’ll find a chicken heart, mild and muscley. Once with a bonus bunch of them from Gippert's Farm I looked for recipes on the Internet and found only pet food ideas. Finally I found a Japanese grilled marinated yakitori and made that—delicious.

We had calves’ liver far too often for me, plain on a plate. It was my bane and my horror until my mother finally gave up trying to get my sisters and me to eat it. I was past my teens before I discovered that disguised in a savory country pâté, liver could be delicious. And my late father-in-law Angelo’s Tuscan crostini--chicken livers cooked with anchovy and capers and pureed on toast--made me a convert.

My father would enjoy the marrow out of chops and braises but I wouldn’t touch it. I regret that now, loving those tender morsels of buttery meaty marrow in osso buco and chops. The other day I scooped roasted beef marrow on toast and topped it with a parsley/shallot/caper/lemon salad, a sublime, beautifully balanced dish from Henderson’s The Whole Beast.

On rarer occasions my mother served pig’s feet (okay, okay, trotters) nestled in a bed of sauerkraut: gooey, porky and tasty. Fortunately they can be found more easily than a lot of other variety meats, and are invariably cheap. I’ve since made them deviled with a mustardy, crumby crust, and Chinese style in a thick sweet sauce of soy and star anise. In Brooklyn I had some killer Caribbean chicken foot souse that was chewy in a good way, tasty and spicy.

The same year that I learned to love liver I first tried tripe (stomach) at a cafeteria in Bologna, Italy. I loved it but even better was my father-in-law’s version, trippa alla fiorentina, basically tripe in tomato sauce but wonderfully tasty and more tender than you’d think. I have to make it once a year or so. In my Brooklyn days I used to lunch regularly on Polish or Dominican versions of tripe soup, hearty and filling, and now I’ve named my blog Tripe Soup, because it’s a universal, worldwide treat and tripe also means nonsense.

Further down the digestive tract are that southern classic chitterlings, or chitlins, made from the same thing that gives sausages their shape, intestines. I have seen them frozen in supermarkets but haven’t yet dared to try cooking them, a process that requires—as you’d imagine--extensive pre-rinsing.

The same year I re-discovered liver and met tripe, I first had blood sausage, cooked by my French aunt who served it with applesauce. The first time she served me some the very thought of it turned me off, but I acquired a taste for the rich stuff and have to have it at least once a year. It goes well with other innards, like in the killer German headcheese called Blut- und Zungenwurst that’s embedded with chunks of tongue, or the Barbadian Puddin’ 'n Souse where a blood and sweet potato sausage is served with pickled pig parts like ears or tails. We ordered some for lunch during a trip to Barbados a few years ago and the proprietor recommended splitting an order because we might not like it. But we each devoured an entire portion with gusto.

Also on that island we had deep-fried milt, a.k.a. “soft roes,” a.k.a. fish semen sacs, quite good, but as the Italians say you could deep-fry an old shoe and it would be good. In the fishy realm, there’s my fish-eye loving five-year-old daughter, the monkfish-liver-loving French, and in China they eat dried fish maw, the air bladder of a conger pike.

Then there are those Rocky Mountain oysters I had at Sticky Fingers in Providence, called in some circles “fries” or “bull balls.” Some men are completely unable to eat them (don’t worry, guys, some people eat cow udders and uteruses, too). Once I asked our server what they were, although I knew the answer already, just to bust her chops. “It ain’t seafood,” was her reply.

More recently I first had sweetbreads, at restaurants, cooked slightly crispy on the outside, creamy within and mild in flavor, a real king among organ meats. But my very favorite of all these spare parts is oxtail. After a three- to four-hour simmer in aromatics, it gets fall-off-the-bone succulent, with an irresistible gelatinousness. I’d like to try the Roman coda alla vaccinara, oxtails stewed with tomatoes and celery and flavored with unsweetened chocolate.

I haven’t yet tried every kind of offal; I still have never had brain, spleen or lung (lights), knowingly anyway, although there may have been some in those hot dogs. According to the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council, though, unless they're labeled as containing variety meats, they contain “muscle meat” just like the ground meat you buy. In Greece they prize kokkoretsi, a sausage made of all the scraps of the sheep: heart, lungs, spleen, liver, sweetbreads, gut and caul fat. In nearby Palermo, Sicily there’s the simpler pani c’a meusa, a spleen sandwich. Brains in brown butter is a classic, and lung is part of the “pluck” essential for haggis, that intriguing Scottish food that contains all the weird parts of the sheep.

Classic Pennsylvania scrapple is made of all those very perishable stray parts of the pig, mixed with cornmeal and seasonings and fried. American tourists in Vienna watch out for Beuscherl mit Serviettenknödel, pig lungs, heart and tongue with dumplings. You have to mix your critters to make dinuguan, a Filipino stew with liver, beef hearts, chicken gizzards and pig's ears and blood, plus garlic, chilies and vinegar.

There are plenty more odd assorted parts from head to foot too numerous to mention here, and since they’re loved worldwide there are hundreds of fascinating classic dishes that call for them. But if you’re still afraid to try them, just think of them next time you bite into a hot dog …Or not.

This column originally ran March 22, 2007, in The Woodstock Times, The Saugerties Times and The Kingston Times, etc.

If you’re a carnivore (if not you’d better turn the page quick), you have likely eaten offal, whether in juicy hot dogs or unctuous foie gras. Otherwise known as variety meats, specialty meats, organ meats, lips and a**holes, entrails, innards, the fifth quarter, quinto quarto in Italian, garbage, scraps, or fodder for Fido.

Although variety meats were popular in tougher times for their frugality, full flavors and pleasing textures, mostly we Americans are afraid of it, liking our meat in the form of nice tidy filets or boneless gristle-less squares that don’t look like they ever came from an animal. So offal has fallen out of favor lately, although it is enjoying a renaissance in cheffy circles. Anthony Bourdain’s Les Halles Cookbook (Bloomsbury, 2004) devotes a whole chapter to “Blood & Guts.” “Chefs get all misty eyed when they talk about it,” says Bourdain, unapologetically offering recipes for veal kidneys á là moutarde and pig heart á l’armagnac.

It’s had to find offal outside of restaurants, though. Although calves’ liver and sometimes tripe and oxtail are around, some things, like brains and lungs, are next to impossible to find. Variety meats are unpopular and don’t keep well, so much of it just goes to the dog food factory. People who live near Chinatowns are in luck, though, as the Chinese are great lovers of varied texture and flavor and specialty meats deliver. Some of them can be challenging to cook compared to steaks and chicken breasts, though, needing blanching (tripe), the briefest cooking (liver), or long slow simmering (oxtail), so some cooks are intimidated by them. “It takes love, and time, and respect for one’s ingredients to properly deal with a pig’s ear or a kidney,” said Anthony Bourdain in Fergus Henderson’s The Whole Beast: Nose to Tail Eating (HarperCollins, 2004). “And the rewards are enormous.”

Innards I have known

When I was a little girl we ate a lot more offal than our neighbors, maybe because of my southern-born parents. They would sometimes buy half a cow to freeze and so we often had beef tongue, which I loved for its mild flavor and fine texture. Later I came to adore dainty jarred pickled lamb tongues and the tongue sandwiches from Carnegie Deli in Manhattan, nearly as good as pastrami. I tried duck tongues at a Taiwanese restaurant in Queens but they were bony and tricky to eat.

Another frequent staple at my childhood table was lamb kidneys with green peppers, which I was never nuts for but would eat anyway. I never see them in stores; maybe people associate them with the urine they process, although supposedly a 12-hour soak in water followed by a 12-24 hour soak in milk solves that problem. Bruce Cost in his Asian Ingredients (Quill, 2000) calls pork kidneys “the world’s most wonderful entrail.”

Whenever my father made fried chicken there would be chewy gristly gizzards to nibble before the big pieces were done, and I loved those. Every Thanksgiving gravy had tiny dices of turkey gizzard and liver and although I detested liver I loved it anyway. I still do my gravy this way. And duck gizzards en confit (cooked in duck fat) are a divine way to top a salad in France.

Sometimes in a bag of gibbies you’ll find a chicken heart, mild and muscley. Once with a bonus bunch of them from Gippert's Farm I looked for recipes on the Internet and found only pet food ideas. Finally I found a Japanese grilled marinated yakitori and made that—delicious.

We had calves’ liver far too often for me, plain on a plate. It was my bane and my horror until my mother finally gave up trying to get my sisters and me to eat it. I was past my teens before I discovered that disguised in a savory country pâté, liver could be delicious. And my late father-in-law Angelo’s Tuscan crostini--chicken livers cooked with anchovy and capers and pureed on toast--made me a convert.

My father would enjoy the marrow out of chops and braises but I wouldn’t touch it. I regret that now, loving those tender morsels of buttery meaty marrow in osso buco and chops. The other day I scooped roasted beef marrow on toast and topped it with a parsley/shallot/caper/lemon salad, a sublime, beautifully balanced dish from Henderson’s The Whole Beast.

On rarer occasions my mother served pig’s feet (okay, okay, trotters) nestled in a bed of sauerkraut: gooey, porky and tasty. Fortunately they can be found more easily than a lot of other variety meats, and are invariably cheap. I’ve since made them deviled with a mustardy, crumby crust, and Chinese style in a thick sweet sauce of soy and star anise. In Brooklyn I had some killer Caribbean chicken foot souse that was chewy in a good way, tasty and spicy.

The same year that I learned to love liver I first tried tripe (stomach) at a cafeteria in Bologna, Italy. I loved it but even better was my father-in-law’s version, trippa alla fiorentina, basically tripe in tomato sauce but wonderfully tasty and more tender than you’d think. I have to make it once a year or so. In my Brooklyn days I used to lunch regularly on Polish or Dominican versions of tripe soup, hearty and filling, and now I’ve named my blog Tripe Soup, because it’s a universal, worldwide treat and tripe also means nonsense.

Further down the digestive tract are that southern classic chitterlings, or chitlins, made from the same thing that gives sausages their shape, intestines. I have seen them frozen in supermarkets but haven’t yet dared to try cooking them, a process that requires—as you’d imagine--extensive pre-rinsing.

The same year I re-discovered liver and met tripe, I first had blood sausage, cooked by my French aunt who served it with applesauce. The first time she served me some the very thought of it turned me off, but I acquired a taste for the rich stuff and have to have it at least once a year. It goes well with other innards, like in the killer German headcheese called Blut- und Zungenwurst that’s embedded with chunks of tongue, or the Barbadian Puddin’ 'n Souse where a blood and sweet potato sausage is served with pickled pig parts like ears or tails. We ordered some for lunch during a trip to Barbados a few years ago and the proprietor recommended splitting an order because we might not like it. But we each devoured an entire portion with gusto.

Also on that island we had deep-fried milt, a.k.a. “soft roes,” a.k.a. fish semen sacs, quite good, but as the Italians say you could deep-fry an old shoe and it would be good. In the fishy realm, there’s my fish-eye loving five-year-old daughter, the monkfish-liver-loving French, and in China they eat dried fish maw, the air bladder of a conger pike.

Then there are those Rocky Mountain oysters I had at Sticky Fingers in Providence, called in some circles “fries” or “bull balls.” Some men are completely unable to eat them (don’t worry, guys, some people eat cow udders and uteruses, too). Once I asked our server what they were, although I knew the answer already, just to bust her chops. “It ain’t seafood,” was her reply.

More recently I first had sweetbreads, at restaurants, cooked slightly crispy on the outside, creamy within and mild in flavor, a real king among organ meats. But my very favorite of all these spare parts is oxtail. After a three- to four-hour simmer in aromatics, it gets fall-off-the-bone succulent, with an irresistible gelatinousness. I’d like to try the Roman coda alla vaccinara, oxtails stewed with tomatoes and celery and flavored with unsweetened chocolate.

I haven’t yet tried every kind of offal; I still have never had brain, spleen or lung (lights), knowingly anyway, although there may have been some in those hot dogs. According to the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council, though, unless they're labeled as containing variety meats, they contain “muscle meat” just like the ground meat you buy. In Greece they prize kokkoretsi, a sausage made of all the scraps of the sheep: heart, lungs, spleen, liver, sweetbreads, gut and caul fat. In nearby Palermo, Sicily there’s the simpler pani c’a meusa, a spleen sandwich. Brains in brown butter is a classic, and lung is part of the “pluck” essential for haggis, that intriguing Scottish food that contains all the weird parts of the sheep.

Classic Pennsylvania scrapple is made of all those very perishable stray parts of the pig, mixed with cornmeal and seasonings and fried. American tourists in Vienna watch out for Beuscherl mit Serviettenknödel, pig lungs, heart and tongue with dumplings. You have to mix your critters to make dinuguan, a Filipino stew with liver, beef hearts, chicken gizzards and pig's ears and blood, plus garlic, chilies and vinegar.

There are plenty more odd assorted parts from head to foot too numerous to mention here, and since they’re loved worldwide there are hundreds of fascinating classic dishes that call for them. But if you’re still afraid to try them, just think of them next time you bite into a hot dog …Or not.